The origins of mankind, the origins of agriculture, and the origins of civilization are three major milestones in the development of prehistoric human societies. During the Late Neolithic (6,000-4,000 years ago), large settlements or central cities, a clear division between rich and poor, the social division of labor and public power emerged in the two river basins (Tigris and Euphrates) in Southwest Asia, the Nile basin in North Africa, the Indus basin in South Asia, and the Yangtze and Yellow River basins in East Asia. This process of social development is known as social complexity and is also referred to as the process of civilization or the origin of civilization. Social complexity meant that in the central settlements or cities there was a large non-agricultural population of artisans, merchants, soldiers, ruling classes, etc. So what agricultural strategy could produce enough food surpluses to feed these non-agricultural populations?

From the available research, the agricultural strategies that have underpinned the process of social sophistication around the world are diverse. In the northern Mesopotamia region of West Asia, agricultural yields were increased mainly by expanding the area under cultivation and reducing inputs per unit area, in an expansionist agricultural model to support urban development; in the Indus region of South Asia, multiple crops were rotated throughout the year to increase agricultural yields to support social development, including locally domesticated millet, rice, and tropical pulses, as well as barley and wheat, which were spread from West Asia.

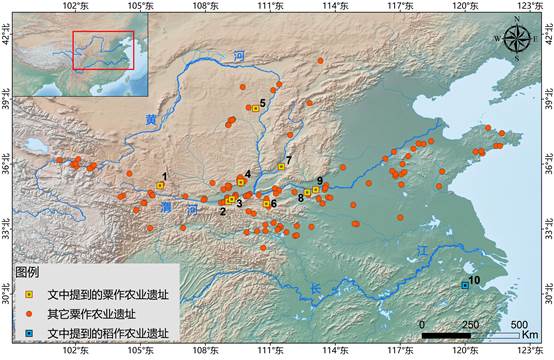

China was one of the central regions in the origin and development of world civilization. Under the influence of the East Asian summer winds, Neolithic China developed an agricultural pattern of southern rice and northern millet, the Yellow River basin in the north was dominated by millet farming, and the Yangtze River basin in the south by rice farming. Under the auspices of the two agricultural systems, northern and southern China began a process of social sophistication during the Late Neolithic (Fig. 1). In the Yellow River basin, the early and middle Yangshao culture (6500-5500 years ago) sites of Hanpo and Jiangzhai already show signs of social sophistication, with large planned settlements, cemeteries, and artifacts symbolizing special power. The late Yangshao culture (5500-5000 years ago), represented by the Dadi Bay, Xiahe, Xipo, and Shuanghuai Tree sites, shows clear signs of social sophistication with large ceremonial buildings, palaces, and hierarchical cemeteries. By around 4,300 years ago, urban centers, represented by the Shihuang and Taosi sites, rose to prominence, culminating in the emergence of a regional state represented by the Erlitou site around 3,800 years ago. In the Yangtze River basin, a regional state represented by the ancient city of Liangzhu had already emerged 5,300 years ago, and archaeological studies of plants show that a single refined rice farming supported the urban development of Liangzhu.

Fig.1Representative sites of social complexity in the Late Neolithic region of China and the distribution of sites of millet farming in the Yellow River Basin

(1, Dadi Bay. 2, Half Slope. 3, Jiangzhai. 4, Xiahe. 5, Shiyuan. 6, Xipo. 7, Taosi. 8, Erlitou. 9, Shuanghuai Tree. 10, Liangzhu.)

Why did a single rice farming operation support the ancient state of Liangzhu? One important reason was the high yield of rice. However, in the Yellow River basin, the two main crops of corn agriculture, corn (commonly known as cereal, called millet after shelling) and millet (commonly known as millets, called yellow rice after shelling), produced less than half of what rice did. Moreover, the main growing areas for corn and millet are on the Loess Plateau, where the soil has a low clay content and organic matter is easily lost, making it impossible to sustain long-term intensive cultivation and requiring fallowing to restore the soil if no fertilizer is applied. Low yields and fallowing have led to a bottleneck in food production for northern corn farming societies. How can yields be increased? Should the area under cultivation be expanded? Or is it better to avoid fallow periods by applying fertilizer?

The environmental archaeology team of Lanzhou University took the Dadi Bay site in Qin'an, Gansu, located on the Loess Plateau in western Longxi Province (Fig. 1) as an object of study, starting from the core elements of the corn farming system - corn, millet and domestic pigs excavated from the site. Nitrogen isotope (δ15N) analysis of charred seeds of corn and millet to trace the fertilization behavior of the farmland revealed that a highly intensive agricultural model had developed at the Dadiwan site 5,500 years ago (Fig. 2): 1) people ate corn and pigs ate lemma husks; 2) domestic pigs were kept in captivity to collect manure; and 3) pig manure fertilized the fields to maintain land strength, avoid fallow and increase yields. This agricultural model is fully consistent with modern sustainable intensive farming models, suggesting that the close combination of corn and millet cultivation and domestic pig rearing in late Neolithic northern Chinese agricultural societies overcame the bottleneck of low corn and millet yields and limited loess fertility, and provided the economic basis for the development of complex societies in northern China at that time. The study was published online on 16 June 2022 under the title 'Sustainable intensification of millet-pig agriculture in Neolithic North China'. "The paper was published online in Nature Sustainability (IF=19.346), a sub-journal of Nature.

Fig. 2Sustainable intensive corn farming systems in Neolithic northern China

The Dadiwan site in Qin'an, Gansu, is a typical Neolithic millet farming site in northern China, comprising a variety of remains from the Pre-Yangshao and Yangshao cultures. A large number of domestic pig bones and charred seeds of corn and millet have been excavated from the site, providing a rich source of research material for this study. Previous studies have found that carbon isotope (δ13C) data from pig bones from late Neolithic corn farming sites in northern China indicate that C4plants (including corn and millet) made up 80-90% of the pig's diet, raising the question of whether pigs and humans consumed corn at the same time and formed a competitive eating relationship. This study revealed that there was no competitive feeding relationship between pigs and humans at the Dadi Bay site, with domestic pigs consuming crop waste -rice husk, and that feeding rice husk to pigs was a strict recipe control behavior, suggesting that domestic pigs were kept in a captive mode, which was more convenient for collecting dung.

Currently, 2.5 billion farmers worldwide are engaged in similar intensive crop-livestock systems, managing 60% of the world's arable land and producing 50% of the world's food. In the context of today's deteriorating natural environment and food crisis, the development of sustainable intensive agriculture in a large number of developing countries and regions remains a key way to safeguard global food security and promote ecological civilization. Survey data from China's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs shows that between 1986 and 2017, the proportion of Chinese farmers adopting similar intensive production models fell from 71% to 12%, and livestock manure is increasingly not being recycled, not only wasting vital resources but also damaging the ecological environment. As Dr. William Burnside, Senior Editor of Nature Sustainability, noted in a commentary on the study, "The development of complex societies and their agricultural bases underlies key challenges we still face", we should draw inspiration from the ancient case of the Neolithic in northern China.

The study also involved archaeologists and plant archaeologists from a number of research institutions, including the Institute of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Gansu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Nanjing Agricultural University, University College London, and the Australian National University. Yang Jishuai, a Ph.D. student in the College of Earth and Environmental Sciences of Lanzhou University, is the first author of the paper, and Professors Yang Xiaoyan and Zhang Dongju are the corresponding and co-first authors of the paper. Academician Chen Fahu, together with Professors Yang Xiaoyan and Zhang Dongju, designed and directed the research. The first author of the paper, Jisai Yang, started the research in his fourth year at university and, in addition to the analysis of archaeological samples, he also tested his conjectures through modern farm fertilization experiments, which took five years from the first data production to the publication of the paper.

Each issue of Nature Sustainability invites authors of one or two papers to write a Research Briefing, which is published online at the same time as the research paper to facilitate a better understanding of important research findings. On behalf of the authors of the paper, Professor Zhang Dongju and Academician Chen Fahu outlined the background, process, findings, and significance of this research under the title "Intensive millet-pig systems supported the rise of complex societies in North China". Professor Gideon Shelach-Lavi, a long-time researcher in Chinese archaeology at the Hebrew University of Israel, reviewed the research findings under the title "How Neolithic farming changed China".

The research team of Lanzhou University in environmental archaeology was established in the 1980s by academician Chen Fahu, and after 30 years of development, it has formed a research team with academician Chen Fahu as the core and national talents such as National Outstanding Youth Fund recipients, Cheung Kong Scholar Distinguished Professors, and Young Cheung Kong Professors as the backbone, which has trained a number of high-quality talents in environmental archaeology. The team has completed the construction of a 14C dating laboratory, photoluminescence dating laboratory, 10,000-grade ultra-clean laboratory (including paleo protein analysis, animal ancient DNA analysis, sediment ancient DNA analysis), plant archaeological laboratory, zooarchaeology laboratory, and isotope archaeology laboratory, and relying on the construction of the laboratory, a series of research results have been published in the fields of human evolution and dispersal, the origin and spread of agriculture, etc. The main results have been published in high-impact journals at home and abroad, such as Nature, Science, PNAS, and Science Bulletin.

Original article: Yang, J., Zhang, D.*, Yang, X.*, Wang, W., Perry, L., Fuller, D. Q., Li, H., Wang, J., Ren, L., Xia, H., Shen, X., Wang, H., Yang, Y., Yao, J., Gao, Y. and Chen, F. 2022.Sustainable intensification of millet-pig agriculture in Neolithic North China. Nature Sustainability, DOI: 10.1038/ s41893-022-00905-9.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-022-00905-9

Research Brief: Zhang, D. and Chen, F. 2022. Intensive millet–pig systems supported the rise of complex societies in North China. Nature Sustainability, DOI: 10.1038/ s41893-022-00907-7.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-022-00907-7

Expert commentary: Shelach-Lavi, G. 2022. How Neolithic farming changed China. Nature Sustainability, DOI: 10.1038/ s41893-022-00899-4.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-022-00899-4#auth-Gideon-Shelach_Lavi